How’s business? We take a thousand-mile journey to find out.

STREET LEVEL

STREET LEVEL

We know what happened on Wall Street, but what’s happening on Main Street, Oregon?

We took a thousand-mile journey around the state to find out.

BY BEN JACKLET

If ever there was a time to take a close look at how the excesses of Wall Street affect the regular people and businesses of Main Street, it is now.

Over the past year, some of the most powerful and sophisticated financial institutions in the world have crashed and burned, plunging the global economy into deep recession and giving rise to fears of an outright depression. The Dow Jones Industrial Average has plummeted from a high in 2007 of more than 14,000 down to the mid 8,000s. Some 5.2 million Americans are expected to lose their homes by 2010. The nation lost 2.6 million jobs last year; 45,400 of those lost jobs were in Oregon.

| {artsexylightbox singleImage=”images/stories/articles/archive/feb2009/slideshow-intro-main.jpg” path=”images/stories/articles/archive/feb2009/slideshow-main”}{/artsexylightbox} |

Clearly Oregon has not sidestepped the downturn, with a statewide unemployment of 9% hovering significantly above the national average. But how do those numbers translate to real life? How well is Main Street, Oregon, holding up? What are the strengths and weaknesses of local economies as the recession deepens and spreads?

I began my inquiry in December in Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River, where 19th century English fur traders introduced global capitalism to Oregon, for better or worse. The first downtown storefront I visited was going out of business. The second was hanging by a thread. The third was closed for the season and possibly forever. By this time it was raining viciously enough to turn Meriwether Lewis into a whiner. From the sound of it, the only action in town was the territorial grunting of the sea lions taking over the waterfront.

This story, I thought to myself, is looking bleak.

Two hours later, I was exploring the interior of the Commodore Hotel with Brian Faherty, who is investing millions in downtown Astoria to fix up old buildings and bring in new commerce. “We’re working with businesses that see the value in moving into a space with character and soul,” he told me.

Faherty must have a lot of faith in the enduring character and soul of Astoria, because when he totaled the downtown storefronts he is investing in, the figure came to 19.

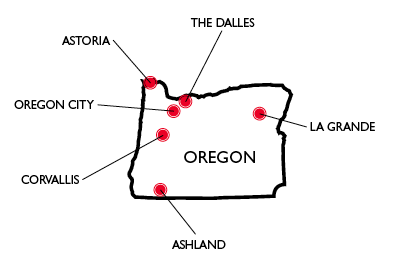

That blend of grim realities and great opportunities would prove to be a powerful theme as I traveled from one downtown to the next, from Astoria to La Grande by way of Oregon City, Corvallis, Ashland and The Dalles. Each of the cities I visited faces ominous, potentially catastrophic trends: rising unemployment, falling fortunes and a dramatic cutback in consumer spending. “For lease” signs outnumber “help wanted” signs by at least a dozen to one. Local governments are struggling with shrinking revenues and a brutal bond market. Major employers are eliminating jobs, new construction has stagnated and vacancy rates are creeping upward. But even the downtown merchants who are hanging on for dear life are unlikely to give in to gloom. The more likely response is to figure out what needs to be done, and do it.

Over the course of my six-city, 1,000-mile tour of Main Street, Oregon, I spoke with a wide variety of shop owners, real-estate agents, restaurateurs, investors, publishers, bookkeepers, entrepreneurs, managers, car dealers, public officials and bartenders. In most cases, our conversations began with a harmless question that has developed urgent new connotations in these times: So, how’s business?

People had more to say on the subject than usual.

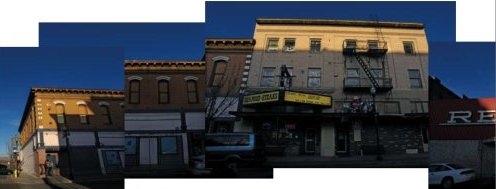

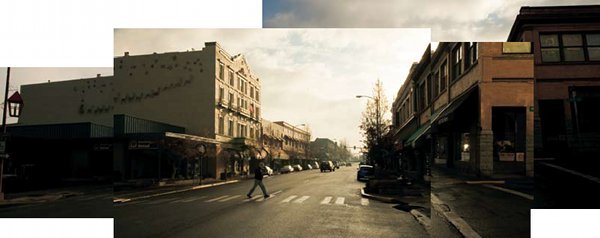

Second Street, The Dalles  PHOTOS BY MICHAEL HALLE |

| ASTORIA |  | Incorporated: 1856 Population: 10,045 Unemployment: 6.7% Median home price: $248,000 Annual cruise ship dockings: 12 |

Brian Faherty and Paul Caruana are investing heavily in downtown Astoria, restoring historic buildings such as the Commodore Hotel on Commercial Street. Brian Faherty and Paul Caruana are investing heavily in downtown Astoria, restoring historic buildings such as the Commodore Hotel on Commercial Street. Lani Donovick opened her Betty Lou Jean Company to tap into Astoria’s growing tourism. Lani Donovick opened her Betty Lou Jean Company to tap into Astoria’s growing tourism.  Anna Lee Larimore at the Blue Scorcher Bakery. Anna Lee Larimore at the Blue Scorcher Bakery. Barista Emily Delay at Coffee Girl, a waterfront café next to the former Bumble Bee fish cannery. PHOTOS BY JUSTIN BAILIE |

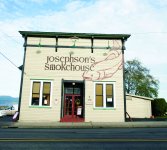

You can’t really call Astoria a logging or fishing town any more, much less a fur-trading outpost. But the city’s colorful past plays a prominent role in its latest economic strategy, to attract tourists and in-migrants with the beauty of its surroundings and its local color, its Starving Artists Faire and Fisher Poets Gathering, its independent bookshops and brewpubs, cafes and theaters. New hotels and condominiums have sprung up along a waterfront serviced by a quaint streetcar. Historic buildings are being refurbished in the city center. The old Bumble Bee tuna cannery has been resurrected as a Rogue Ales brewpub. A dozen cruise ships are scheduled to dock at Astoria’s Pier One in 2009.

In many ways, the city’s makeover has been a success. Even on a typically stormy winter afternoon, the two central streets that define Astoria’s downtown, Commercial and Marine, exude a lively vibe. The recession hasn’t kept the bike-to-coffee crowds away from the Astoria Coffeehouse, which sells pumpkin spice lattes for $3.75 and breakfast cookies for $2.25. Foot traffic is steady outside of locally owned businesses such as Amazing Stories Comic Books and Games, Fulio’s Italian Restaurant and the Wet Dog Brewpub.

That’s the scene that brought Brian Faherty into Astoria. He and his partners are developing four downtown properties simultaneously, spending $4.5 million on purchases alone. They bought the Commodore Hotel for $565,000 and are putting $1.5 million into restoring a former ferry hotel into a groovy hangout for visiting urbanites.

“Our model is to restore the building back to its original architectural features and then fix up the interiors,” he says. “We’ll rent the storefront for a little more money, but businesses will have a better chance of succeeding because they won’t have to spend constantly on improvements.”

So far the model appears to be working, based on the sharp new digs for the Astoria Co-op and others. But filling the remaining spaces may prove daunting. It’s looking like a long winter for downtown businesses that bet on the continued upward mobility of Astoria.

“People are just hiding, or at least they’re hiding their wallets,” says John Williams, store manager for the upscale JP Plumbing Co., which boasts a large “clearance sale” sign near its entrance. “How bad it will get, we won’t know until it’s all over.”

The recession has already cost downtown Astoria several newcomers, including the promising retailer Urban Funk II. Other businesses are scrambling to avoid a similar fate. Lani Donovick opened the Betty Lou Jean Company on Marine Drive in August to tap into downtown’s rising fortunes. But her timing and price point — $200 jeans in Astoria — couldn’t have been less fortunate. “I feel like I’m filling a market niche,” she says during a long lull between customers. “But the economy is what it is.”

The same applies to the real estate market, which powered Astoria’s growth but has sputtered and stalled. Prices are down 11% and business is slow at AREA Properties, a prominent business on Commercial Street and a key advertiser in the Daily Astorian.

“We’ve had a lot of realtors leave the market,” says Kathren Rusinovich, the listing agent seven townhomes at Columbia Landing, along the formerly industrial waterfront. But at $460,000-$645,000 per home, it’s looking like a tough sell. Buyers may plunge in eventually, adding to the vibrancy of Astoria, but not in the midst of a recession.

|

| ASHLAND |  | Incorporated: 1874 Population: 21,630 Unemployment: 8.7% Median home price: $390,000 Annual theater productions: 780 |

Take a seat at a cafe near the corner of First and Main in downtown Ashland, even during the off-season, and you’ll be hard-pressed to find any evidence of a false economy disintegrating. There are few vacancies on this Main Street, much less boarded-up storefronts or going-out-of-business sales. The flow of pedestrians is a soothing constant, locals and visitors wandering from one locally owned business to the next.

Ashland is not attempting to recreate itself as a tourist destination. It has a 70-year history as a tourist destination. Since the Oregon Shakespeare Festival was created here (in the middle of the Great Depression) in 1935, Ashland’s Main Street has developed into a cultural oasis, a magnet for retiring seniors who made their fortunes in California and a college town that embraces the buy-local ethic and runs chain stores out of town. Even the real estate market has held up relatively well, compared to the flood of foreclosures that has swamped nearby Medford.

But these are not the best of times to be catering to the wealthy. The Shakespeare Festival missed its budget by $750,000 in 2008 and is slashing $1 million in costs in 2009. Local retirees are spending more carefully, given the 30% losses many investment funds racked up in 2008.

Tom DuBois, who runs the local Grilla Bites franchise, a low-cost, fast-food joint, says he first began noticing well-dressed, refined customers frequenting his restaurant during last summer’s festival. “They would order soup and salads and water,” he says, shaking his head. “These are folks who might normally be spending $100 over at Chateaulin.”

Tom DuBois, who runs Grilla Bites in Ashland, is glad he’s not trying to sell expensive dinners right now.  PHOTOS BY JAMIE LUSCH |

Chateaulin Cuisine Francaise and Wine Shop has been a Main Street attraction for 35 years. Owner Jason Doss says the 2008 summer season was OK, but the winter holiday parties dropped off significantly, and wine sales are way down. “I’ve got customers who come in every year and buy 10 cases of wine. This year they are buying five. It’s better not to ask why. I just say, ‘Thank you very much.’”

Doss worries that many of Ashland’s retailers, gallery owners and restaurateurs are barely hanging on. “Some of them, I’ll be surprised if they make it through the winter.”

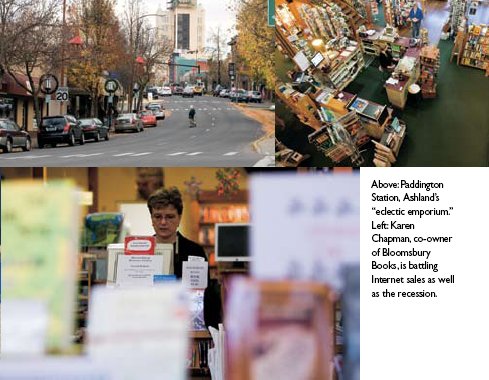

Even Ashland’s more affordable icons are feeling it. Karen Chapman, co-owner of Bloomsbury Books on East Main, says sales are down 15%. Her part-time staffers have voluntarily cut back on their hours, and she’s reduced store hours.

More ominous still are the sleepy-looking half-dozen real estate storefronts in downtown Ashland. The number of licensed realtors in the Rogue Valley has dropped from 1,150 to about 850, and the survivors are scrambling to master the complex art of selling homes for less than is owed on the mortgage. “Three years ago half of our realtors weren’t interested in short sales,” says Collin Mullane, principal broker for the Ashland REMAX office. “You don’t have a choice any more.”

Shop owners are also working harder for slimmer rewards. Pam Hammond, co-owner of Paddington Station, “Ashland’s eclectic emporium,” toiled from 10 a.m. until midnight on a recent weekday to capitalize on the bankruptcy of one of her major suppliers. She says it was worth it because it enabled her to buy quality merchandise for pennies on the dollar.

In her previous career, Hammond managed 45 locations for May Department Stores. As hard as it gets in independent retail, she says she has no regrets. “I am thankful I’m not working for a big company. We’re small, but we’re diversified and we can respond quickly to take advantage of trends in the market.”

But independent retailers will never beat chains on price, and price matters more than ever, even in Ashland. “Our visitor count has held steady or even grown,” says former mayor John Morrison. “But people just aren’t spending as much as they used to.”

| CORVALLIS |  | Incorporated: 1860 Population: 54,890 Unemployment: 5.6% Median Home Price: $246,000 Music shops: 7 |

Walk down the main street of Corvallis, Southwest Second Avenue, and the word recession doesn’t spring to mind. From one end of town to the other, this street bustles with bookshops and bike shops, music stores and clubs, brew pubs and cafes. Thick crowds line up for fairly traded coffee at the Beanery and locally brewed ginseng porter at the Old World Deli.

At the center of town, Robnett’s Hardware, the oldest store in the Northwest, is packed with customers. The same family has run Robnett’s since 1853, surviving countless downturns, including the Great Depression. “The community has been great about supporting us,” says store manager Scott Lockwood during a rare pause between assisting customers and ringing up sales. “People are very loyal to us, so we must be doing something right.”

No Main Street is recession-proof, but college towns are better positioned than most, thanks to the disposable incomes of students and the ideals and ideas of tenured faculty, who enjoy enviable job stability and benefits. The state’s $900 million higher education budget is actually expected to increase by 5% during the next biennium. In addition, one of Oregon’s proposed tactics to jump start the economy involves tackling deferred maintenance at public universities to create jobs immediately.

But even Corvallis is feeling the recession at the upper end of the price scale. One attractive downtown storefront, Forrest Temple Lighting, recently went out of business after five years of selling custom lighting systems and imported furniture. “I was undercapitalized,” owner Shawn Graham explains as customers browse through the last of his discounted inventory. “I used all the profits to keep the business going. I didn’t have any reserves.”

An even pricier development next door to Graham’s former store, 7 Stones Holistic Spa, is facing similar realities. Owner Deanna Carr spent three and a half years building the perfect setting for $175 facials and $60 pedicures inside a LEED-certified three-story building with a wine bar on the top floor. Her spa opened in April, just as the recession was beginning to clamp down on consumer wallets. She has had to reduce prices and offer creative specials. “People are focusing on their needs rather than their wants,” she says. That’s a bad trend for her nascent business, but she says she remains “absolutely committed to adapting rather than contemplating the worst.”

The recent experiences of Graham and Carr serve as warnings to the entrepreneurs and investors who hope to create mini-Pearl Districts. The fall-off in conspicuous consumption is no joke. It is a real shift, with deep consequences. Graham recognized this while watching his business dissolve once the credit vanished. “The economy we built was not real,” he says. “It was a false economy. Everybody was living in a fool’s paradise.”

| THE DALLES |  | Incorporated: 1860 Population: 13,045 Unemployment: 7.7% Median home price: $175,000 Radio Station storefronts: 5 |

|

The signs of weakness in downtown The Dalles don’t just consist of the “for lease” signs that dot Second Street, the main drag. There’s also a sign posted on the entrance to Columbia River Bank titled “Your Safe Harbor,” a reassuring note to depositors from a bank that has seen its stock price fall by nearly 90% over the past year.

Downtown recently lost a pet shop, a jeweler, a cleaning supplies shop and a shoe store. More independent retailers are expected to tumble once Walmart completes its new superstore on the outskirts of town.

Debbie Bryan, manager of Tony’s Town and Country Clothing and a resident of The Dalles for 30 years, says Walmart is the last thing downtown merchants need. Bryan says sales are down 20% at Tony’s, and shoppers are so hungry for deals they try to haggle for bargains when they aren’t price-checking before heading home to shop online. “We’re going to lose more shops downtown this winter,” she predicts. “I just don’t see how they’re going to make it.”

But The Dalles has a knack for bouncing back from hardship. The most recent example was the collapse of the aluminum industry, which employed 2,000 people locally. In the wake of that loss, The Dalles has rebuilt itself by luring Google with cheap electricity and investing heavily in its port to create manufacturing jobs. The Wasco County unemployment rate of 7.7% for November was lower than the statewide average. Downtown has vacancies but is by no means dead, with a new French Restaurant, a pair of new tattoo parlors, and some successful start-ups.

One example is Geekster Computers, a 2-year-old family business that repairs old computers and custom-builds new ones, called Geek Boxes. “We’ve sold three just today,” says co-owner Colleen Derryberry. “And our repair business is taking off. Everybody needs their computer, and unfortunately computers aren’t going to stop breaking. We’re seeing more people coming in to fix their computers instead of purchasing new ones.”

A similar return to do-it-yourself frugality has benefited other downtown businesses, such as A’s Sewing Shoppe. It has also helped longtime institutions such as the Dalles Chronicle to do more with less. The paper’s publisher, Marilyn Roth, routinely joins the distribution team to help out with bundle drops. “People in small towns know how to hunker down and weather the storm,” she says.

That would seem to be an encouraging trend — so long as “hunkering down” means more than simply buying cheap at Walmart while the downtown core crumbles. Some merchants fear that will happen. Others are confident it won’t.

Count Dave Toupal among the confident. He and five partners run Red Wagon Antiques, where business has never been brisker. “People will always have disposable income for antiques,” he says.

Really?

“You name it, there’s somebody out there who collects it. Bottle caps. Winchesters. Custom jewelry. Coins. Uniforms. Anything that has to do with the military, especially World War I or World War II. Or Hawaiian. We can’t keep anything Hawaiian in the store. We increased our hours recently because business has been so good.”

Really?

“Really.”

Washington Street, The Dalles  PHOTOS BY MICHAEL HALLE |

| LA GRANDE |  | Incorporated: 1865 Population: 12,850 Unemployment: 9.5% Median home price: $130,000 Miles of nearby hiking trails: 1,700 |

Too many Main Streets have seen their old theaters torn down, or sadly converted into drug stores or insurance offices. But in the middle of downtown La Grande, the hub of northeastern Oregon, the Granada Theatre is alive and well.

Relatively well, that is. “The big movies still bring people out, but you can definitely tell that the entertainment dollar is something people are cutting back on,” says manager Edna Henderson. “You have to remember how many people are out of work in this town.”

Unemployment in surrounding Union County shot up from 6.4% last September to 9% in October, then increased again to 9.5% in November as Boise Cascade and local trailer manufacturers cut back production. The sudden loss of jobs is an unexpected development for La Grande, which usually fares better than other remote economies east of the Cascades because of the stabilizing presence of Eastern Oregon University. Other trends here are equally troubling. Real estate sales are down by a third. A 21,000-square-foot office building right in the middle of Adams Street is selling for just $300,000.

One of the oldest family businesses in downtown La Grande, the M.J. Goss Motor Company, established in 1922, has posted a sign out front proclaiming, “When you buy from us, you give the whole town a lift.” Inside his office, third-generation owner Mark Goss takes a break from signing bills to shake his head and sigh, “It’s been a tough year.”

Some local merchants trace La Grande’s decline to the arrival of box stores in general and Walmart in particular. “Walmart has devastated our downtown,” says Julie Bodfish, owner of a 65-year-old family business Fitzgerald Flowers. “The last 10 years have been a constant nosedive.”

Still, Bodfish’s business seems to be doing all right, especially considering the $80 teapots and $6 packets of candy she’s selling. Sales are down but not dramatically, and she subleases to renters to bring in additional revenue and has diversified by doing more events.

“The few of us that are left down here are fairly good at what we do,” she shrugs.

A few blocks away, Trish Zennie and Nancy Dake echo this theme. They launched their spa, Body Work, in the worst of economic times but business has been “doing nothing but grow,” Zennie says. “We’ve kept our costs as low as possible by basically doing everything ourselves. We work nights and weekends and we don’t spend money if we don’t have to. For a long time we didn’t even have a phone or a sign out front.”

Another factor, adds Dake: “They don’t offer discount massages at Walmart.”

Rather than accepting that the local economy is collapsing, Dake and Zennie prefer to characterize it as changing. Jeff Clark, a young realtor with John L. Howard & Associates, shares that glass-half-full view. Clark recently returned to La Grande from a stint in the Peace Corps, and his passion spills over as he sprints through a list of local attributes: the newly established Satellite Gallery, the long-awaited Mt. Emily Alehouse, the annual Solstice Triathlon, the great mountain biking and motorcycle touring, the La Grande Summer Festival, just to name a few. “It’s definitely a time of change for La Grande, and I’m very positive about what’s coming.”

| OREGON CITY |  | Incorporated: 1844 Population: 30,060 Unemployment: 7.2% Median home price: $280,000 Local tailors in 1844: 4 |

Left: Jeannette Helley of Madco Draperies, Main Street Oregon City. Right: AndyBusch says he is having to reinvent his family furniture business “daily. |

Oregon City’s downtown is the oldest city center west of the Mississippi, and the first impression from street level is that it’s seen better days. Rents hover at about half of the going rate in Metro Portland, and even so, vacancies abound. The Oregon City Bicycle Repair Shop, a Main Street fixture since 1908, is gone. The Clackamas County Courthouse, which generates most of the local foot traffic, could be on its way out.

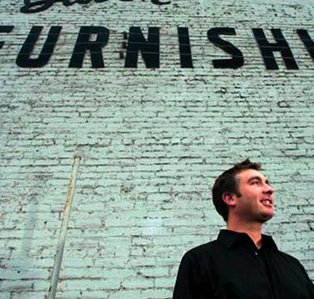

Robb Crocker of Funnelbox Motion Picture Studios has invested in four buildings in Oregon City. |

There are some businesses that appear to be holding up just fine. Andrew Hopp, the fourth-generation proprietor of Hopp’s Custom Upholstery, is hustling from one job to the next. Donuts are disappearing at Muno’s Bakery. The Depot Barbershop is packed with walk-ins.

But it’s a slow morning for big-ticket retailers such as Tom Busch Home Furnishings, established in 1885. “We’re reinventing ourselves daily,” says Andy Busch, sitting in a showroom stocked with a million dollars worth of merchandise but no customers. Busch has tried optional Mondays for his five employees and started buying on consignment and even doing his own deliveries, driving to the coast in one recent trip. His chief consultant on these moves has been his 80-year-old grandfather, Tom Busch, Sr., who led the business through the Great Depression.

Fortunately, the family owns the building and the furniture. “It’s all paid for,” says Andy Busch. “If we need to flip the switch and go to auxiliary power, we can do it.”

A few storefronts down, Jeannette Helley of Madco Draperies is also feeling fortunate to own rather than lease. “That’s the only way we have been able to survive,” she says.

Helley had expected her small mother-daughter shop to be busy through June filling a major order for the Bandon Dunes golf resort on the coast. But that order is on hold. More importantly, so is the sale of her building. She had found a buyer and planned to move to Damascus. But the buyer backed off because tenants have been hard to find.

Grim stuff. Still, before you write off Oregon City, you’d better meet Robb Crocker, the 34-year-old CEO of Funnelbox Motion Picture Studios at 712 Main St. He has grown his business from three to 13 employees since moving from downtown Portland to Oregon City in 2005. Given that growth, Crocker says he isn’t too worried about the recession. “I see it as an opportunity to gain market share,” he says.

Crocker is not only hoping other creative firms will follow him to Oregon City and its cheap Main Street rents; he is gambling on it. He and a silent partner have spent $4 million to buy four buildings on Main Street. Between their efforts and those of another young investor, Ryan Smith, a whole new Main Street is taking form, one Crocker compares to Portland’s Pearl District, complete with a wine bar, a gourmet pizza joint, an advertising agency, and a coming-soon upscale bar and restaurant.

“I see huge potential in Oregon City,” Crocker says. “We can build a whole new creative community here.”

It remains to be seen whether Oregon City will transform itself; whether a time of change or decay lies ahead for La Grande; whether downtown Ashland can hold onto its aura as the money slows; and how well The Dalles will withstand its latest economic setback.

The question of how the meltdown on Wall Street will impact Oregon’s main streets is both simple to answer and impossible to know. The inescapable truth is that no business district is immune to global recession, especially as job losses continue their epidemic spread. Sales will drop, businesses will go under and vacancy rates will rise. This is already happening. The moribund real estate and mortgage storefronts found at the center of most Oregon downtowns serve as visual reminders that Wall Street and Main Street aren’t nearly as separate and unrelated as we may have wished.

More unfortunate evidence of the relationship between Wall Street and Main Street can be found in the municipal bond market. The banking behemoths that specialize in backing city infrastructure have their own troubles; two of the biggest, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, are defunct. The surviving bond buyers are playing cautious hardball, bad news for all cities and especially bad for smaller, more remote cities that have not earned strong bond ratings.

Another weakness that became clear during my travels involves consumer spending. Everywhere I went, the story was consistent: Customers are still coming in, but they are spending less. Frugal Oregonians may interpret this as a rational return to living within one’s means, but there is a very real threat that cash-hording shoppers will retreat to the big box chain stores, leaving Main Streets to wither. The commitment to buying locally is deeply embedded in Oregon, but that ideal will be hard pressed to overpower the urge to save money as the job losses and insecurity spread.

That said, there’s no shortage of great local businesses that will power through this recession as they have previous downturns. Community institutions such as Robnett’s Hardware in Corvallis, the Ashland Springs Hotel and the Red Cross Drug Store in La Grande survived the Great Depression by building strong reputations and making adjustments quickly and intelligently. These businesses and many others who are well established and debt-free are certain to outlast this slump as well. Some will benefit from the weakness of their competitors to expand.

It is tempting to gloss over the crisis by recasting it as a grand opportunity for positive transformation. It’s true that depressed real estate prices will enable some investors to move into Main Street and reinvigorate it with new ideas. But exciting, transformative ideas don’t always add up to profits. The courageous few who are investing optimistically in these times are taking big risks. Even Brian Faherty, the visionary developer hoping to tap into and transform the soul and character of Astoria, confided, “This may not be the smartest thing I’ve ever done.” However, he added quickly, “It’s what I like to do.”

The greatest temptation of all is to look for salvation in Keynesian stimulus packages, such as Governor Kulongoski’s jobs and transportation package and President Obama’s yet-to-be-determined but certain-to-be-ambitious federal stimulus package. Both the governor and the president have vowed repeatedly to put the interests of Main Street before those of Wall Street, to create jobs and restore economic vitality,

State and federal investments are crucial because local coffers are already stretched thin. Even when times are good, Oregon cities spend more time in the red than the black. According to the League of Oregon Cities, 147 cities representing 2.3 million people spent more than $200 million more than they brought in during the fiscal year ending June 30, 2007. And those were the good days, when building permits were pouring in, unemployment was low and the municipal bond market was solid. Now that the economic indicators have changed for the worse, local governments will be hard pressed to provide the basic services that keep Main Streets viable, much less vibrant. Already Eugene is facing an $8 million shortfall, Madras has one third fewer cops than in 1996 and a third more people to protect and serve, and Klamath Falls has seen funding dry up for $50 million of city street projects.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re talking about Ashland or Burns,” says Linda Ludwig, deputy legislative director of the League of Oregon Cities. “For most cities in Oregon, the resources aren’t keeping up with the costs of providing services.”

The cold, hard facts do not bode well for the historic city centers of Oregon. The businesses that give downtowns their character and soul will need to use every ounce of ingenuity and support they can muster to hold onto what they have built collectively over 150 years.

Fortunately, ingenuity and support are hardly endangered qualities in Oregon’s central business districts. How else can you explain the antiques dealer in The Dalles expanding hours to keep up with demand, the spa in La Grande that has done nothing but grow since opening amid global economic meltdown, the Oregon City investor with visions of creating another version of Portland’s Pearl District?

There’s grit on Oregon’s main streets. It’s helped them get this far, and it will keep them alive.

Have an opinion? E-mail [email protected]